Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CF - Housing Report - Final - Embargoed 7.11.14

Uploaded by

wtopwebOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CF - Housing Report - Final - Embargoed 7.11.14

Uploaded by

wtopwebCopyright:

Available Formats

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

Commissioned by The Community Foundation for the National Capital Region with generous support from The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation.

Prepared by the Urban Institute and the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

July 2014

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

AUTHORS

Leah Hendey

Peter A. Tatian

Graham MacDonald

With the assistance of

Kassie Bertumen, Brittany Edens, Rebecca Grace, Brianna Losoya, and

Elizabeth Oo from The Urban Institute; and Hilary Chapman and Sophie

Mintier from the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

Above and cover photos: Matt Johnson

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank The Community Foundation for the National Capital Region and

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation for their generous support in funding this study.

The authors would also like to thank and acknowledge the assistance and contributions of the

following in completing this study:

Silvana Straw, The Community Foundation for the National Capital Region

Jacqueline Prior, The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation

Karen FitzGerald, The Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Foundation

Alison McWilliams, Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation

Martin Mellett, Jubilee Housing

David Bowers, Enterprise Community Partners

Members of the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments Homeless Services Planning

and Coordinating Committee and Housing Directors Advisory Committee

Public agency staf and key stakeholders from nonprot housing advocates, service providers, and

nonprot developers who consented to be interviewed for this study.

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary ....................................................................................... vi

The Regions Income Distribution .................................................................. vi

The Homeless System ...................................................................................... vii

Afordable Rental Housing ............................................................................... ix

Afordable Homeownership ............................................................................. x

Funding Afordable Housing and Homeless Services ................................ xi

Conclusion ......................................................................................................... xii

1. Introduction ............................................................................................... 2

The Regions Income Distribution .................................................................. 4

Continuum of Housing ..................................................................................... 8

2. The Homeless System .............................................................................. 9

How Many Homeless People Live in the Region? .................................... 12

What is the size of the homeless population

in each jurisdiction? .............................................................................................. 13

What is the gender and age composition

of the homeless population? ............................................................................ 14

How many homeless adults are employed

and what is the most common source of income? ................................... 14

How Many Beds Are in the Regions Homeless Systems? ........................16

Are There Enough Beds to Meet the Need? ............................................... 18

Immediate need for shelter ............................................................................... 18

Need for permanent housing ........................................................................... 18

Providing permanent supportive housing decreases

homelessness and eases the shortage of shelter beds .............................. 21

What Local Policies and Practices Might Address the Need? ................... 22

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

3. Afordable Rental Housing .................................................................... 25

How Many Households Need Afordable Rental Housing? .....................25

How Many Afordable Rental Units Exist? .................................................. 29

Programs that increase rental unit afordability ............................................ 30

Are There Enough Rental Units to Meet the Need? ................................. 33

What Local Policy Tools Are Available

to Jurisdictions to Increase Afordability? .................................................. 38

Inclusionary zoning .............................................................................................. 38

Accessory dwelling units .................................................................................... 39

Other regulatory policies ................................................................................... 40

4. Afordable Homeownership ................................................................. 41

How Many Households Need Afordable

Homeowner Housing? ................................................................................... 43

How Many Afordable Homeowner Units Exist? ...................................... 46

Are There Enough Units to Meet the Need? .............................................. 47

Tools and Policies Available to Promote

Afordable Homeownership ......................................................................... 50

Home purchase assistance ................................................................................ 50

Home rehabilitation and repair ......................................................................... 50

Housing education and counseling ................................................................ 51

Inclusionary zoning .............................................................................................. 51

Real property tax relief ......................................................................................... 52

5. Funding for Afordable Housing and Homeless Services ................ 53

Public Funding Sources for Housing Services ........................................... 54

Housing trust funds ............................................................................................. 55

Public Spending on Housing ......................................................................... 57

Philanthropic Spending on Housing ............................................................ 62

How much did funders contribute to housing-related

organizations which provide services

in the Washington region? ................................................................................. 62

What is the distribution of housing-related

funding by jurisdiction and type of service? .................................................. 64

What role did Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

play in the region? ................................................................................................ 67

6. Conclusion ............................................................................................... 68

References .................................................................................................... 70

References for Public Funding ...................................................................... 72

Appendix A: Comparative and Summary Proles

for the Washington Region and Its Jurisdictions ...................................73

Appendix B: Glossary of Terms ................................................................. 86

Appendix C: The Regions Housing-Related

Nonprot Sector ......................................................................................... 89

Appendix D: Budget Analysis Categories .............................................. 103

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION vi

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

1 The following jurisdictions in the Washington region are included in the analysis: District of Columbia; Montgomery and Prince Georges counties

in Maryland; Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William counties and the cities of Alexandria, Fairfax, Falls Church, Manassas, and Manassas

Park in Virginia.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The shortage of afordable housing in

the Washington region is becoming

increasingly clear. Without better

information on the supply and

demand for housing, however, it

is extremely difcult for the public,

private, and philanthropic sectors to

make strategic investments or data-

driven policy decisions to reduce

homelessness and make housing

more afordable. To address this

information gap, The Commu-

nity Foundation for the National

Capital Region, with support

from The Morris and Gwendolyn

Cafritz Foundation, commissioned

this study of housing afordabil-

ity in the Washington region.

1

This study, prepared by the Urban

Institute and the Metropolitan

Washington Council of Governments,

examines the entire continuum of

housing, from the emergency shelter

system to afordable homeowner-

ship opportunities. It documents

how housing patterns and policies to

address needs across the continuum

vary by local jurisdiction. This is the

rst study in many years to compre-

hensively examine the continuum

of housing needs across the region.

This study also uniquely examines

how housing policies and programs

are funded in the region, including

the support they receive from both

the philanthropic and public sectors.

THE REGIONS INCOME

DISTRIBUTION

Although the Washington region

is home to some of the wealthiest

counties in the country, many house-

holds are still struggling to get by on

minimum- or low-wage jobs. In 2013,

Washington, DC, had the second-

highest costs for a four-person family

among all cities, according to the

Economic Policy Institute (2013).

TABLE ES.1. HUD INCOME LIMITS BY HOUSEHOLD SIZE FOR THE WASHINGTON REGION, 2011

Income Category 1-Person 2-Person 3-Person 4-Person

Extremely low income (at or below 30% of AMI) $22,300 $25,500 $28,700 $31,850

Very low income (at or below 50% of AMI) $37,150 $42,450 $47,750 $53,050

Low income (at or below 80% of AMI) $47,350 $54,100 $60,850 $67,600

Middle income (at or below 120% of AMI) $89,200 $102,000 $114,800 $127,400

Source: US Department of Housing and Urban Development Income Limits.

vii HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

In 2011, the area median income (AMI)

was $106,100 for a family of four. Table

ES.1 shows the income categories

the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) uses in its

subsidy programs to dene afordabil-

ity for diferent types of households.

In the Washington region, about

one-third of households had low,

very low, or extremely low incomes

(table ES.2). Insufcient income is a

signicant barrier for many people in

obtaining and remaining in afordable

housing. The District of Columbia

had the highest share of lower-

income households in the region

at 46 percent, while in Arlington,

Fairfax, and Loudoun, fewer than

25 percent of all households were

lower-income. (The data discussed

throughout this study are available

in summary proles for the region

and by jurisdiction in Appendix A

and online at http://www.urban.

org/publications/413161.html.)

THE HOMELESS SYSTEM

Homelessness is the most extreme

consequence of a lack of afordable

housing and permanent supportive

housing options in the region. People

become homeless for many reasons,

including insufcient income, job

and health insurance loss, rising

rents, physical and mental disabilities,

and domestic violence. This study

covers three categories of homeless:

(1) the sheltered homeless, (2) the

unsheltered homeless, and (3) the

chronically homeless, who may be

sheltered or unsheltered. Although

most are homeless for a few months

or less, a small group, the chroni-

cally homeless, has been homeless

for years. Increasing the supply of

afordable rental units and perma-

nent supportive housing would

reduce homelessness in the region.

Key ndings on the homeless

system include:

In January 2013, 11,245 people

were homeless in the Washington

region, including 5,944 single adults

and 5,301 people in families.

2

The District of Columbia had more

homeless people than the other

seven jurisdictions combined.

Nearly three in four homeless

single adults were male, while

four in ve homeless adults in

families were female (and the

majority were single parents).

Single adult households were

made up almost entirely of persons

age 25 and older (85 percent),

while 72 percent of all persons in

family households were children

or young adults (under age 25).

Thirty-six percent of homeless

adults in families in the region

were employed. In Alexan-

dria, Arlington, and Loudoun

County, more than two-thirds

of homeless adults in families

2 Data from the 2014 Point-in-Time Count of the homeless were not available when the analysis for this study was conducted. Findings based on

2013 data are consistent with conclusions that might be drawn from the 2014 data. The regions homeless population grew by 399 people, or 3.5

percent, between the 2013 and 2014 counts. The regional increase was largely attributable to a 13 percent rise in homelessness in the District of the

Columbia. The 2014 homeless population included a slightly higher share of people in families49 percent compared to 47 percent in 2013.

TABLE ES.2. HOUSEHOLDS IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

BY INCOME LEVEL, 200911

Income Level Total Percent

Extremely low 229,500 13.0

Very low 201,300 11.4

Low 145,200 8.2

Middle 529,600 29.9

High 663,700 37.5

Total Households 1,769,400 100.0

Source: American Community Survey, 200911

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION viii

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

3 The 2,219 additional permanent supportive housing beds for single adults and 180 for families are minimum estimates of the need based on

the 2013 data. Additional beds may be needed to accommodate the recent rise in homelessness, particularly in the District of Columbia, future

demand, and the typically low turnover rate for occupants of permanent supportive housing.

were employed. In the District of

Columbia and Prince Georges,

less than one-third of homeless

adults in families were employed.

Most homeless people lived in

emergency shelters or transitional

housing. Approximately 11 percent

(1,259) of the homeless popula-

tion lived on the streetlargely

single adults. With the exception of

Alexandria, no suburban jurisdic-

tion could meet the immediate

shelter needs of this group. Even

if all available shelter beds were

occupied, the region would still fall

short of meeting the shelter needs

of homeless single adults by 467

beds. One in four homeless per-

sons was chronically homeless; an

increase in permanent supportive

housing would reduce homeless-

ness among this population. The

Washington region would need at

least 2,219 additional permanent

supportive housing beds for single

adults and 180 for families to meet

the needs of its chronically home-

less population (table ES.3).

3

Almost

all of the regions chronically home-

TABLE ES.3. BEDS NEEDED TO MEET THE PERMANENT SUPPORTIVE HOUSING NEEDS OF THE CHRONICALLY

HOMELESS IN THE WASHINGTON REGION BY JURISDICTION, 2013

Single Adults Persons in Families

Chronically

homeless

Available

beds

Gap

(surplus)

Chronically

homeless

Available

beds

Gap

(surplus)

District of Columbia 1,764 275 1,489 263 9 254

Montgomery 222 5 217 6 62 (56)

Prince Georges 73 4 69 24 43 (19)

Alexandria 69 2 67 5 0 5

Arlington 156 68 88 0 0 0

Fairfax 243 26 217 10 12 (2)

Loudoun County 28 0 28 0 0 0

Prince William 47 3 44 2 4 (2)

Washington region 2,602 383 2,219 310 130 180

Source: Urban Institute analysis of Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments 2013 Point-in-Time Count of the homeless.

ix HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

less families were in the District of

Columbia and Prince Georges.

Most homeless persons in families

and single adults did not need

permanent supportive hous-

ing, however. Rather, many just

needed afordable rental housing

and, in some cases, additional

supports, such as assistance with

securing child care, health insur-

ance and employment, to help

them hold a lease and maintain

rent payments over time. Increas-

ing the supply of rental housing

afordable for extremely low

income households would reduce

homelessness in the region.

AFFORDABLE RENTAL

HOUSING

Rental housing must address the

needs of a diverse range of house-

holds across all income levels,

including, for example, elderly

people on xed incomes, lower-

income working families, and young

professionals just starting their

careers. The recent housing crisis

forced many households out of

homeownership and brought about

tighter lending standards that made

home mortgages more difcult

to obtain. This further strained an

already overstretched rental sector

in the Washington region. Renters

with extremely low incomes are

particularly challenged in nding

afordable housing in the region, but

afordability problems extend to very

low, low, and even many middle

income households. Lower-income

renters frequently face enormous

competition from higher-income

households for scarce aford-

able units. In all jurisdictions, the

median rental unit is unafordable to

workers with extremely low incomes,

such as those earning minimum

wage and low-wage workers.

Key ndings on rental housing

include:

Although renter households

accounted for only 37 percent of

all households in the Washington

region in 200911, they made

up the majority of lower-income

households, including 58 percent

of very low income households

and 70 percent of extremely

low income households.

Almost half of all renter households

in the region have struggled with

high housing costs, including more

than 150,000 households with

severe housing cost burden (i.e.,

households that pay more than half

their income on rent and utilities).

HOMELESS CATEGORIES

HomelessPeople who are

currently without permanent

housing, including both sheltered

and unsheltered homeless.

Sheltered homelessPeople

residing in shelters, safe havens,

or transitional housing.

Unsheltered homelessPeople

living on the street or in places

not meant for human habitation

such as abandoned buildings,

bridges, parks, and campsites.

Chronically HomelessAn adult with

a disabling condition who has either

been continuously homeless for at

least a year, or has had at least four

episodes of homelessness in the past

three years. The chronically homeless

may be sheltered or unsheltered.

Household Types

Adult-only households

Single, homeless adults.

Family householdsHomeless

families consisting of at least one

adult and one child (under age 18).

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION x

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

Eighty-six percent of extremely

low income renter households

were cost-burdened, paying more

than 30 percent of their income

on housing, including 72 percent

who were severely cost-burdened.

The most unafordable rents were

in Arlington, where 91 percent

of extremely low income renters

were cost burdened. Prince William

(90 percent), Fairfax and Prince

Georges (88 percent) followed.

Extremely low income renters

faced enormous competition for

afordable units. Higher-income

households occupied 40 percent

of the units that would have been

afordable to the poorest ten-

ants, producing a regional gap of

more than 94,000 rental units for

extremely low income households.

No jurisdiction had enough aford-

able and available rental units to

meet the demand by extremely

low income households, with

gaps ranging from 3,500 units

in Loudoun to 22,100 units in

the District of Columbia.

Very low and low income house-

holds also faced competition

for afordable units from higher-

income renters. Forty-six percent

of units afordable for very low

income households and 50 percent

of units afordable for low income

households were rented by higher-

income households. Consequently,

77 and 52 percent of very low

and low income households,

respectively, were cost-burdened.

Montgomery and Fairfax had too

few afordable and available units

for very low income households.

The District of Columbia, Prince

Georges, Prince William and Lou-

doun lacked sufcient numbers of

units for low income households.

The Washington region had only

enough public housing units and

vouchers to serve about one

in three extremely low income

households. The District of

Columbia was home to nearly half

of the regions HUD-subsidized

units and more than one-third

of the regions afordable units

that were funded with low

income housing tax credits.

AFFORDABLE

HOMEOWNERSHIP

Homeownership is an important

part of the regional housing market

because it helps support stable

communities and allows house-

holds to build wealth. Despite the

recent housing crisis, homeowner-

ship remains an important means

for low and middle income house-

holds to save by building equity in

their homes and to maintain stable

housing in retirement. In most of the

region, however, average sales prices

are signicantly higher than what

is afordable for many households,

causing homeownership to decline

and presenting a signicant barrier

to many who would benet from

owning their home. At the time of

the study, lower-income households

made up only one-fth of the regions

homeowners. To respond to these

challenges, jurisdictions throughout

the Washington region have put in

place diferent policies and programs

to promote sustainable homeowner-

ship and to reduce the nancial and

other barriers to owning a home for

lower-income buyers. These include

home purchase assistance, home

rehabilitation and repair, housing

education and counseling, inclusion-

ary zoning, and property tax credits.

Key ndings on homeownership

include:

Sixty-three percent of households

in the Washington region were

homeowners in 200911. However,

xi HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

homeownership afordability in the

region declined between 2000 and

2011 as housing prices increased by

32 percent, adjusted for ination.

For low income homebuyers,

the average home sale price was

48 percent higher than what

they could aford. Homeowner-

ship was most afordable for

rst-time homebuyers in Prince

Georges and Prince William and

was least afordable in the Dis-

trict of Columbia, Montgomery,

Arlington, Alexandria, and Fairfax.

Almost one-third (31 percent) of

owner-occupied households in

the region paid more than 30

percent of their monthly income

in housing costs, with cost

burden rates that ranged from

88 percent for extremely low

income households to 10 percent

for high income households.

There were approximately 1.14

million homes (owned or for sale)

in the region, most of which were

afordable only to middle or high

income rst-time buyers. For low

income rst-time homebuy-

ers, 75 percent of these homes

would not be afordable without

assistance. Prince Georges had

the highest share of afordable

units relative to its share of the

regions homeownership stock,

followed by Prince William.

Lower-income households in

the Washington region faced

competition from higher-income

households for afordable homes.

Nearly seven in ten units afordable

to very low income households and

two-thirds afordable to low income

households were occupied by

someone in a higher income cat-

egory. This competition contributed

to a gap of 56,800 afordable units

for very low income owner house-

holds and a gap of 22,600 aford-

able units for low income owners.

FUNDING AFFORDABLE

HOUSING AND

HOMELESS SERVICES

In an increasingly resource-

constrained environment, particularly

at the federal level, it is important to

understand the current sources of

funding and identify where additional

funding could be generated to

address the afordable housing gaps

in the region. While the Washington

region nances many housing-

related programs and services with

funding from many federal programs,

county and city money accounted

for the majority of public funding

for housing-related expenditures

in all jurisdictions except for Prince

Georges, Fairfax, and the District

of Columbia. In addition, the local

philanthropic sector provided impor-

tant support to housing-related

nonprots throughout the region. The

loss of local charitable giving from

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the

Freddie Mac Foundation, however,

further challenges already stretched

budgets and funding streams.

Key ndings on funding for aford-

able housing and homeless services

include:

Federal programs were an

important source of funding for

housing-related activities in the

Washington region. In addition,

most jurisdictions drew signi-

cantly on county and city funds,

particularly Arlington, Alexandria,

and Prince William where more

than half of public funding for

housing was from these sources.

Federal spending on housing, such

as the Community Development

Block Grant and HOME program,

is not likely to increase in the near

term to ll the gaps in afordable

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION xii

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

housing in the Washington region.

Local jurisdictions will need to nd

innovative ways to produce more

afordable housing through zoning

ordinances and regulatory policies

or by raising revenue to ll the

gaps, potentially by leveraging local

resources through housing trust

funds or ofering tax-exempt bonds.

Overall, $1.3 billion was budgeted

in FY 2013 for housing-related

expenditures in the Washington

region. The greatest expenditures

were for rental assistance. The

region collectively allocated nearly

$637 million to Section 8, Hous-

ing Choice Vouchers, and other

rental assistance programs in 2013.

The second-largest budgeted

item was housing production

and preservation, followed by

programs related to homelessness,

senior housing, tenant services,

and homebuyer assistance.

The District of Columbia accounted

for approximately 50 percent of all

the housing-related expenditures

in the region, with Montgomery

spending the second-highest

amount, followed by Fairfax.

The private philanthropic sector in

the Washington region awarded

more than $33.4 million in grants

to housing-related organizations,

primarily nonprot organizations, in

2012. Private philanthropic invest-

ment was relatively small compared

with public spending on housing in

FY 2013 ($1.3 billion). Three-quarters

of philanthropic grants were for

less than $50,000, and three in ve

grant dollars were for homeless

prevention, shelter, or services and

transitional or permanent support-

ive housing. Nearly half of the hous-

ing-related private funding went

to organizations whose service

area was the District of Columbia.

Montgomery was next, receiving

about 10 percent of the total.

Of concern, nearly half of private

grant funding, and the majority

of grants larger than $100,000,

were disbursed by Fannie Mae,

Freddie Mac, and the Freddie Mac

Foundation, which largely ceased

charitable giving in 2013. The loss

of their charitable giving leaves a

large gap in funding for nonprot

organizations, particularly for those

providing homeless prevention

services, shelter, transitional and

permanent supportive housing, or

foreclosure prevention services.

CONCLUSION

This study analyzes the supply of

and gaps in afordable housing

across many housing needs and

household types. The continuum of

housing needsfrom basic shelter to

supportive housing, from a subsidized

apartment to an afordable home

for saleencompasses housing for

homeless individuals and families,

Photo: Matt Johnson

xiii HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

for renters, and for homeowners.

To provide for households at difer-

ent points along the continuum,

the federal government, state and

local jurisdictions, private investors,

and philanthropic organizations

have created several public and

private programs and supports to

promote the creation and preser-

vation of afordable housing.

Despite the current eforts and

investments, however, this study

identies many important gaps in the

housing continuum that highlight

the acute need for more afordable

housing in the Washington region.

The region has long been among the

most expensive metropolitan areas

nationally, and housing has become

increasingly unafordable for many

households in recent years. Although

the area has generally higher incomes

and wages than most other places in

the country, incomes are not keeping

pace with rising housing costs.

As a result, homelessness remains

a persistent problem; over 11,000

persons have been counted living on

the streets or in homeless shelters,

including many children and persons

in families. The supply of permanent

supportive housing needed to reduce

chronic homelessness is insufcient

to meet the current demand. The lack

of afordable rental apartments across

all income levels, and particularly

for extremely low income house-

holds, contributed to the numbers of

homeless people and also resulted

in over half of the regions renters

paying over 30 percent of their

income on housing costs, which

leaves them less money for food,

medicine, and other essentials.

Finally, homeownership, which is the

path to savings and stability for most

people living in the United States, is

out of reach for many in the region.

In many cases, homeownership is

out of reach not for a lack of steady

income, but because high prices

fueled by excessive demand squeeze

potential buyers out of the market.

Providing shelter and decent,

afordable housing for persons at

all income levels is a goal that a

prosperous area like the Washington

region should be able to achieve.

Furthermore, to remain competi-

tive, the region must address

housing afordability to ensure

that its workforce can continue

to nd housing without having to

commute farther and farther to

work. Without stable housing in a

decent environment, it is difcult

for many to secure a quality educa-

tion, good health, and employment.

Policymakers are paying increasing

attention to afordable housing as a

platform for connecting households

with other supports and services

that can help them achieve better

outcomes. The region may bear

additional costs down the road, such

as higher incidences of social disrup-

tion, crime, and unemployment, if

housing instability is not addressed.

Understanding the importance of

afordable housing and the needs

in this region, foundations commis-

sioned this study to quantify the need

for afordable housing and inform

strategic investments by the philan-

thropic sector all along the housing

continuum. This study contains a

wealth of information that can also

help jurisdictions better identify and

address the nature of the afordable

housing needs in their own commu-

nities and be used for evidence-based

planning. The study documents

the acute need for both permanent

supportive housing for the chronically

homeless and afordable housing

across all income levels, particularly

for extremely low income renters

and low income homebuyers. These

ndings can be used to direct scarce

public and private sector resources to

the populations most in need of relief

from high housing costs and to build

and preserve afordable housing for

these households over the long term.

Detailed data for each

jurisdiction can be found in

the summary and compar-

ative proles in the appen-

dices of this study. These

proles and additional data

are also available online

at http://www.urban.org/

publications/413161.html.

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION 2

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

1. INTRODUCTION

The shortage of afordable housing in

the Washington region is becoming

increasingly clear. However, without

better information on the supply and

demand for housing, it is extremely

difcult for the public, private, or

philanthropic sectors to make strate-

gic investments or data-driven policy

decisions to reduce homelessness

or improve housing afordability.

To address this information gap,

the Community Foundation for the

National Capital Region, with support

from The Morris and Gwendolyn

Cafritz Foundation, commis-

sioned the Urban Institute and the

Metropolitan Washington Council

of Governments to complete this

comprehensive study of housing

afordability in the Washington region.

While many studies cover individ-

ual housing issues, this is the rst

comprehensive study in many years

to examine the entire continuum of

housing from the emergency shelter

system to afordable homeown-

ership opportunities across the

Washington region, including a review

of housing policies and programs

and sources of funding. It identies,

both at a regional and a jurisdictional

level, the supply of and demand

for emergency shelters, homeless

prevention programs, transitional

housing, permanent supportive

housing, rental housing, and owner

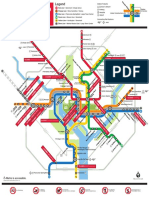

housing (see gure 1.1 for a map of

the jurisdictions and the text box for

more information). The study also

looks at how housing patterns and

policies to address needs across the

continuum vary by local jurisdiction.

This study uniquely examines how

housing policies and programs are

funded in the Washington region,

quantifying the level of support they

receive from both the public and the

philanthropic sectors. The analyses

use several quantitative and quali-

tative data sources including the

American Community Survey, juris-

dictions budgets, an extensive scan

of jurisdictions websites, and inter-

views with public agency staf and

key stakeholders, such as nonprot

housing advocates, service provid-

ers, and nonprot developers.

The study contains six sections. This

rst section describes household

incomes in the region. Sections

24 discuss the homeless system,

afordable rental housing, and

afordable homeownership. These

sections examine the gap or surplus

of housing units and how policies

and programs vary across jurisdic-

tions. Section 5 examines how

housing programs and services are

funded in the region, including both

public and philanthropic spending.

JURISDICTIONS IN THE WASHINGTON, DC, METRO AREA INCLUDED IN STUDY

District of Columbia

Maryland: Montgomery and

Prince Georges counties

Virginia: Arlington, Fairfax,

Loudoun, and Prince William

counties and the cities of

Alexandria, Fairfax, Falls Church,

Manassas, and Manassas Park.

Where relevant, information on

the independent housing policies

of the following jurisdictions in

Maryland is included: Gaithersburg,

Rockville, Takoma Park, Bowie,

College Park, and Greenbelt.

Photo: E.L. Malvaney

3 HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

Charles

Fauquier

Frederick

Loudoun

Fairfax

Montgomery

Stafford

Calvert

Spotsylvania

Prince George's

Warren

Clarke

Prince William

Jefferson

District of Columbia

Arlington

Alexandria

Manassas

Fredericksburg

Fairfax City

Manassas Park

Falls Church

Jurisdictions in the study

Other jurisdictions in the metro area

FIGURE 1.1. MAP OF THE WASHINGTON, DC, METROPOLITAN AREA AND THE JURISDICTIONS INCLUDED

IN THE STUDY

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION 4

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

4 Because many programs that subsidize the cost of housing use the eligibility criteria of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD), those criteria from 2011 are used for this study. HUDs income limits are based on the AMI for a family living in the Washington, DC,

metropolitan area. The Washington, DC, metropolitan area refers to the statistical area dened by the Ofce of Management and Budget, which

in 2011 included 22 jurisdictions. All other references to the Washington region refer to the designated study jurisdictions as shown in gure 1.1.

5 For more detailed explanation, see http://www.huduser.org/portal/pdrdatas_landing.html.

THE REGIONS INCOME

DISTRIBUTION

Although the Washington region

is home to some of the wealthiest

counties in the country, many house-

holds are still struggling to get by

on minimum or low-wage jobs.

4

In

2011, the area median income (AMI)

was $106,100 for a family of four in

the Washington, DC, metropolitan

area (that is, 50 percent had incomes

less than $106,100 and 50 percent

had incomes that were higher). This

study uses ranges based on AMI used

by the US Department of Housing

and Urban Development (HUD) (see

table 1.1) to categorize households

and the cost of housing units. Please

note that upper income limit for low

income (at or below 80 percent of

AMI) is lower than one might expect.

HUD caps the ofcial 80 percent of

AMI limit, which may not exceed the

median income for the United States.

5

Therefore, although the AMI in 2011

was $106,100, the 80 percent limit

for a family of four in the Washing-

ton region was $67,600, or about 64

percent of AMI, instead of $84,880,

which would be the full 80 percent.

The study employs the follow-

ing conventions when referring to

income categories: extremely low

income are households whose

annual income falls between 0 and

30 percent of AMI, very low income

are those between 30 and 50 percent

of AMI, low income households are

those between 50 and 80 percent

of AMI; middle income households

have incomes between 80 percent

and 120 percent of AMI, and high

income households are those earning

more than 120 percent of AMI.

TABLE 1.1. HUD INCOME LIMITS BY HOUSEHOLD SIZE FOR THE WASHINGTON REGION, 2011

Income limit 1-Person 2-Person 3-Person 4-Person

Extremely low income (at or below 30% of AMI) $22,300 $25,500 $28,700 $31,850

Very low income (at or below 50% of AMI) $37,150 $42,450 $47,750 $53,050

Low income (at or below 80% of AMI) $47,350 $54,100 $60,850 $67,600

Middle income (at or below 120% of AMI) $89,200 $102,000 $114,800 $127,400

Source: US Department of Housing and Urban Development Income Limits.

5 HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

TABLE 1.2. INCOME AND WAGES FOR THE WASHINGTON-ARLINGTON-ALEXANDRIA, DC-VA-MD-WV

METROPOLITAN AREA, 2011

2011 Income ($) Max. afordable monthly

2011 Area median income: $106,100 Rent ($)

Homeowner

costs ($) Hourly Annual

Extremely Low Income (at or

below 30% of AMI)

15.31 31,850 800 740

Maryland and Virginia minimum wage 7.25 15,080 380 350

DC minimum wage 8.25 17,160 430 400

Parking lot attendants 10.63 22,100 550 520

Poverty level 10.75 22,350 560 520

Food preparation workers 10.82 22,510 560 530

Proposed DC, MD minimum wage

6

11.50 23,920 600 550

Nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants 13.80 28,700 720 670

Receptionists 14.55 30,260 760 710

Very Low Income (at or below 50% of AMI) 25.50 53,050 1,330 1,240

Bookkeepers 20.98 43,640 1,090 1,020

Paramedics or emergency medical technicians 22.31 46,400 1,160 1,080

200% of poverty level 21.49 44,700 1,120 1,040

Postal service mail carriers 25.10 52,210 1,310 1,220

Low Income (at or below 80% of AMI) 32.50 67,600 1,690 1,580

Fireghters 27.16 56,500 1,410 1,320

Kindergarten teachers 27.97 58,170 1,450 1,360

Police and sherif's patrol ofcers 30.65 63,760 1,590 1,490

Middle Income (at or below 120% of AMI) 61.25 127,400 3,190 2,970

Registered nurses 36.30 75,500 1,890 1,760

Fireghting supervisors 40.57 84,380 2,110 1,970

Dental hygienist 43.49 90,460 2,260 2,110

High school administrator 49.93 103,850 2,600 2,420

High Income (above 120% of AMI)

Human resources managers 62.85 130,740 3,270 3,050

Chief executives 74.88 155,750 3,890 3,630

Lawyers 96.64 201,010 5,030 4,690

Note: Data are rounded to the nearest $10. All income limits and poverty levels used are those for a four-person family.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates; HUD Income Limits; US Department of Health and Human

Services Poverty Guidelines; and Urban Institute calculations.

INCOME CATEGORIES

The income categories listed

here are used throughout

the study unless otherwise

specied. Income limits vary

based on household size; the

ranges shown below represent

the HUD income limits in 2011

for a household of four people.

Extremely low income:

households whose annual

income falls between 0 and

30 percent of area median

income (AMI) ($0$31,850)

Very low income:

3050 percent of AMI

($31,850$53,050)

Low income: 5080 percent

of AMI ($53,050$67,600)

Middle income:

80120 percent of AMI

($67,600$127,400)

High income: More

than 120 percent of AMI

(Above $127,400)

6 Under a joint proposal from ofcials in the

District of Columbia and Montgomery and

Prince Georges counties, the minimum

wage would increase to $11.50 by 2016 in

these jurisdictions (Davis 2013).

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION 6

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

Table 1.2 shows the maximum rent

persons at the top of each income

category could aford if they were

paying 30 percent of their income

in rent each month (30 percent is

considered afordable by experts).

The table also shows the maximum

monthly homeowner costs, calcu-

lated at 28 percent of income

(industry standard underwriting

limit). However, within each income

category, the maximum monthly

payment list in the table is unaford-

able for many families. For example,

the maximum afordable rent for

household at 30 percent of AMI

($31,850) is $800. A household

that is extremely low income but

is at 20 percent of AMI would only

be able to aford rent of $530.

Using information on the wages

of various occupations in the

Washington, DC, metropolitan area,

this study estimates the maximum

afordable housing costs for families

with workers employed in various

occupations (see table 1.2).

7

For

example, a family with a single

worker earning minimum wage in

Maryland and Virginia would be able

to aford only about $380 in rent

each month, while a reghter in

these states could aford $1,320 in

homeowner costs each month.

In the Washington region, more

than one in three households were

high income in 2011, earning more

than $127,400 annually (table 1.3).

About one-third of the nearly 1.8

million households in the region

had low, very low, or extremely low

incomes. The District of Columbia

had the highest share of lower-

income households in the region

at 46 percent, while in Arlington,

Fairfax, and Loudoun, fewer than

25 percent of all households were

lower-income.

8

(The data discussed

throughout this study are available

in summary proles for the region

and by jurisdiction in Appendix A

and online at http://www.urban.

org/publications/413161.html).

Lower-income households difered

in several ways from those of middle

and high income households (table

1.4). For example, across the region,

63 percent of all households were

homeowners. Of those, only one-fth

were lower-income. Between 30

and 49 percent of lower-income

households were homeowners.

Lower-income households were

also more likely to be made up of a

single adult than were higher-income

TABLE 1.3. HOUSEHOLDS IN

THE WASHINGTON REGION BY

INCOME LEVEL, 200911

Income level Total

Per-

cent

Extremely low 229,500 13.0

Very low 201,300 11.4

Low 145,200 8.2

Middle 529,600 29.9

High 663,700 37.5

Total

households

1,769,400 100.0

Source: American Community Survey,

200911.

7 Data on wages and occupations is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics program and reects

wages for all workers in a given occupation. See http://www.bls.gov/oes/.

8 This study uses analysis of 200911 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata from the University of Minnesota Integrated Public Use

Microdata Series. It uses Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMA) as the geography of reference. The PUMA that includes Fairfax County also includes

Fairfax and Falls Church cities. The PUMA that includes Prince William County also includes Manassas and Manassas Park cities and the PUMA

that includes Loudoun County also includes Clarke, Fauquier, and Warren counties. All data using the American Community Survey in this study

are based on these PUMA denitions.

7 HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

9 Moderate or severe disabilities are those that limit mobility or ones ability to care for oneself.

10 These data account only for the elderly in households and do not count elderly people who are living in group quarters, such as nursing homes.

Frail elderly are those with moderate or severe disabilities.

households. Nearly one-half of

extremely low-income households

had only one member compared

with 18 percent of high-income

households. Family households with

children represented about one-third

of all households in the region, a

share that is roughly constant across

income categories. Family house-

holds without children (consisting

of two or more related adults) and

nonfamily households (such as

two unrelated adults) were more

prevalent among higher-income

than lower-income households.

Vulnerable individuals or those

requiring special housing are more

common among lower-income

households. Lower-income house-

holds were more likely than higher-

income households to have an

elderly member or someone with

moderate or severe disability (table

1.4).

9

In the Washington region,

about 20 percent of households

had a member age 65 or older, 4

percent had a frail elderly member,

and 8 percent had a member with

moderate or severe disabilities.

6

For

extremely low income households,

the percentages were approxi-

mately 1.5 to 2.0 times higher.

An important element of housing

afordability in addition to rent levels

or home prices is whether house-

hold members are working and

the wages that they earn. Across all

income groups, 81 percent of house-

holds had at least one member who

was working full time. But again,

extremely low income households

are outliers. In those households, only

TABLE 1.4. HOUSEHOLD CHARACTERISTICS IN THE WASHINGTON REGION BY INCOME LEVEL, 200911

Income Level

Category

Extremely

low

Very

low Low Middle High Total

Homeownership rate 30 42 49 63 83 63

Percentage of household

members:

With elderly member 28 24 21 18 16 20

With member with moderate

or severe disabilities

18 12 9 7 5 8

With frail elderly member 9 6 5 4 2 4

With one or more full-

time workers

37 73 82 87 93 81

With no full-time workers,

one or more part-time worker

19 10 6 4 3 6

No one working

(all adults are over 65)

21 13 9 7 3 8

Pct. no one in household

working (at least one

working-age member)

23 5 3 2 1 5

Source: American Community Survey, 200911.

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION 8

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

11 This only includes students living in households; students living in dormitories are counted as part of the group quarters population and are not

reected in this study.

12 CNHED. (2011, September 26). Meet the Continuum of Housing. Retrieved from http://www.cnhed.org/blog/2011/09/

meet-the-continuum-of-housing

37 percent had at least one person

working full time. That rate is consid-

erably lower than even very low

income households (73 percent) and

low income households (82 percent)

(table 1.4). A higher share (21 percent)

of extremely low income households

had adults 65 or older who might be

considered retired than other house-

holds. This also makes them more

vulnerable to afordability issues.

Most concerning, almost one-fourth

of extremely low income house-

holds had no working household

members even when family members

were of working age. Higher disabil-

ity rates for these households may

partially explain this higher rate of

nonworkers or non-full-time workers.

Extremely low income households

may also include individuals attend-

ing school or job training, thus

temporarily forgoing employment.

11

CONTINUUMOF HOUSING

In its 2010 report, An Afordable

Continuum of HousingKey to a

Better City, the Coalition for Nonprot

Housing and Economic Development

(CNHED) describes the broad range

of housing needs for diferent popula-

tions and income groups in the

District of Columbia. Later, CNHED

used this framework to launch the

Housing for All Campaign to promote

a range of housing choices that are

available to people.

12

The concept of

the continuum of housing is relevant

to housing security across the region,

and it is applied here to analyze

the supply and gaps across many

housing needs and household types.

The continuum of housing needs

encompasses the homeless, renters,

and homeowners. At diferent points

along the continuum, households

need diferent types of housing, from

emergency shelter to a market-rate

home. To support households along

the continuum, the federal govern-

ment, state and local jurisdictions,

private investors, and philanthropic

organizations have created many

public and private programs and

supports. At the very lowest income

levels (up to 50 percent of AMI),

individuals and families very likely

need a signicant subsidy and support

to be housed adequately. Housing at

this end of the continuum includes

emergency shelter and permanent

supportive housing for those who

are homeless or at risk of becoming

homeless, and public housing

and Housing Choice Vouchers

for others. The latter substantially

subsidize the costs of housing

extremely low income households.

Households slightly higher on the

income ladder also benet from

subsidy programs. Indeed, as the

data in this study show, households

with very low or low incomes can

face severe housing cost burdens in

the Washington region. In addition

to public housing and Housing

Choice Vouchers, subsidized options

include privately-owned housing

created though programs such as

Section 8, Section 202 (supportive

housing for the elderly), Section 811

(supportive housing for persons with

disabilities), low income housing

tax credits (LIHTC), and Federal

Housing Administration nancing.

As households move up the

income spectrum, purchasing a

home becomes an increasingly

viable option. Because of the high

housing prices in many parts of the

Washington region, homeownership

is out of reach for many households

without additional nancial and other

supports. As with rental housing,

federal, state, and local governments

have created policies and programs

to encourage homeownership and

lower the barriers to purchasing a

home for those with lower incomes.

These include lower-cost mortgages,

tax credits, homebuyer education

and counseling programs, and home

repair and rehabilitation assistance.

The next section examines the most

vulnerable families on the contin-

uumthose who are homeless or

at risk of becoming homeless.

9 HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

2. THE HOMELESS SYSTEM

In January 2013, 11,245 people

were homeless in the Washington

region, including 5,944 single adults

and 5,301 people in families.

13

The District of Columbia had more

homeless people than the other

seven jurisdictions combined.

Nearly three in four homeless single

adults were male, while four in ve

homeless adults in families were

female (and the majority were single

parents). Single adult households

were made up almost entirely of

persons age 25 and older (85 per-

cent), while 72 percent of all persons

in family households were children

or young adults (under age 25).

Thirty-six percent of homeless

adults in families in the region were

employed. In Alexandria, Arlington,

and Loudoun County, more than

two-thirds of homeless adults in fami-

lies were employed. In the District of

Columbia and Prince Georges, less

than one-third of homeless adults in

families were employed.

Most homeless people lived in

emergency shelters or transitional

housing. Approximately 11 percent

(1,259) of the homeless population

lived on the streetlargely single

adults. With the exception of Alexan-

dria, no suburban jurisdiction could

meet the immediate shelter needs

of this group. Even if all available

shelter beds were occupied, the

region would still fall short of meet-

ing the shelter needs of homeless

single adults by 467 beds. One in

four homeless persons was chroni-

cally homeless; an increase in per-

manent supportive housing would

reduce homelessness among this

population. The Washington region

would need at least 2,219 additional

permanent supportive housing beds

for single adults and 180 for families

to meet the needs of its chronically

homeless population.

14

Almost all

of the regions chronically home-

less families were in the District of

Columbia and Prince Georges.

Most homeless persons in families

and single adults did not need

permanent supportive housing,

however. Rather, many just needed

afordable rental housing and, in

some cases, additional supports,

such as assistance with securing child

care, health insurance and employ-

ment, to help them hold a lease

and maintain rent payments over

time. Increasing the supply of rental

housing afordable for extremely low

13 Data from the 2014 Point-in-Time Count of the homeless were not available when the analysis for this study was conducted. Findings based on

2013 data are consistent with conclusions that might be drawn from the 2014 data. The regions homeless population grew by 399 people, or 3.5

percent, between the 2013 and 2014 counts. The regional increase was largely attributable to a 13 percent rise in homelessness in the District of

the Columbia. The 2014 homeless population included a slightly higher share of persons in families: 49 percent compared to 47 percent in 2013.

14 The 2,219 additional permanent supportive housing beds for single adults and 180 for families are minimum estimates of the need based on

the 2013 data. Additional beds may be needed to accommodate the recent rise in homelessness, particularly in the District of Columbia, future

demand, and the typically low turnover rate for occupants of permanent supportive housing.

HOMELESS CATEGORIES

HomelessPeople who are

currently without permanent

housing, including both sheltered

and unsheltered homeless.

Sheltered homelessPeople

residing in shelters, safe havens,

or transitional housing.

Unsheltered homelessPeople

living on the street or in places

not meant for human habitation

such as abandoned buildings,

bridges, parks, and campsites.

Chronically HomelessAn adult with

a disabling condition who has either

been continuously homeless for at

least a year, or has had at least four

episodes of homelessness in the past

three years. The chronically homeless

may be sheltered or unsheltered.

Household Types

Adult-only householdsSingle,

homeless adults.

Family householdsHomeless

families consisting of at least one

adult and one child (under age 18).

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION 10

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

income households would reduce

homelessness in the region.

Homelessness is the most extreme

outcome caused by a lack of afordable

housing and permanent supportive

housing options in the region. People

become homeless for many reasons,

including insufcient income, job

loss, rising rents, domestic violence,

loss of health insurance, and physical

and mental disabilities. They are also

homeless for diferent lengths of

time. Although most are homeless for

less than six months, a small group,

the chronically homeless, has been

homeless for years (US Department

of Housing and Urban Development

2013). Recent research shows that the

most efective remedies target the root

causes of an individuals homelessness

and the length of time they have been

homeless (Rog et al. 2014).

This chapter reviews shelter needs,

the supply of beds, and the regions

capacity to meet the needs of its

homeless population. The study

covers three categories of homeless

(see the sidebars for denitions

of the terms used in this section):

(1) the sheltered homeless, (2) the

unsheltered homeless, and (3) the

chronically homeless, who may be

SHELTER & HOUSING SYSTEM

Continuum of Care (CoC)A group

of local government agencies and

nonprot service providers that

administer programs to prevent and

end homelessness in a particular

jurisdiction. There are nine CoCs in

the Washington region.

ShelterIncludes on-demand

emergency and winter shelters

for homeless people. Shelters are

intended to be a temporary, short-

term solution before transitioning to

a more permanent housing option.

Safe HavenA 24-hour residence

that serves homeless individuals with

severe mental illness who have been

unable or unwilling to participate in

supportive services. The facilities place

no requirement of receiving social

services or treatment on residents, but

instead introduce services gradually as

the residents are ready.

Transitional HousingShort-to-

medium-term accommodations

(typically fewer than two years) for

homeless individuals.

May also include services to assist

individuals and families with moving

to permanent housing.

Permanent Supportive HousingA

model that provides permanent, fully-

subsidized housing in combination

with supportive servicessuch as

substance abuse treatment, case

management, and job trainingto

chronically homeless individuals and

families with barriers to achieving

independence such as mental illness,

substance abuse, or HIV/AIDS.

Housing FirstAn approach to ending

homelessness, pioneered in 1988,

in which homeless individuals or

families are moved immediately from

a shelter or the streets to their own

apartment. Housing First programs

rst priority is to stabilize people in the

short-term and help them get housed

immediately (Lanzerotti 2004).

Needed social services are provided

after stable housing is in place and,

unlike past approaches to solving

episodes of homelessness, receipt of

services is not required for individuals

or families to remain in housing.

Rapid Re-HousingA set of programs

that grew out of the Housing First

approach to provide housing search

and temporary nancial assistance to

quickly end a period of homelessness

by moving people into permanent

housing. The National Alliance to

End Homelessness (2014) identies

three core components of a Rapid

Re-Housing program: housing

identication; rent and move-in

assistance; and case management

and services. Rapid Re-Housing

can also refer to a specic HUD

grant program, The Homelessness

Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing

Program, which provides nancial

assistance and services to both

prevent individuals and families

from becoming homeless and to

help those who are experiencing

homelessness to be quickly re-housed

and stabilized. Rapid Re-Housing

can be a particularly efective

strategy for persons who become

homeless due to a short-term

economic crisis. See http://portal.

hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/

recovery/programs/homelessness.

11 HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

sheltered or unsheltered.

15

Formerly

homeless are not included in this

study nor are youth living on their

own; the latter because of the dif-

culty in counting homeless youth.

The study also considers two distinct

household types: adult-only house-

holds (referred to as single adults) and

family households. For a discussion on

youth homelessness please see the

Homeless Youth box on page 12.

Addressing homelessness requires

both temporary and permanent

housing solutions. In the short term,

unsheltered homeless individuals, for

example, need immediate housing,

and jurisdictions rely on emergency

shelters or transitional housing that

may include some supportive services

to address their needs. Chronically

homeless individuals, in contrast,

need permanent supportive, subsi-

dized housing with services such as

case management, job training, and

treatment for physical and mental

health conditions. Both unsheltered

and sheltered homeless adults and

families who are not chronically

homeless less often need more inten-

sive services such as those provided

in permanent supportive housing,

but they can benet from short-

term services to help them keep up

with rent payments in the long term

or case management services to

connect them to available benets,

job training, and other supports. More

often they need afordable rental

housing options, including rental

subsidies such as public housing

and Housing Choice Vouchers

(discussed in Section 3 of this study).

Increasingly, jurisdictions are

adopting a Housing First approach

to homelessness, which moves

individuals and families immediately

or as quickly as possible into perma-

nent housing. Once an individual

or household is stably housed, the

service provider ofers supportive

services, although participation is not

required to maintain housing. In the

Washington region, all jurisdictions

take a Housing First approach, but

they are in various stages of transi-

tioning from more traditional models

that focused on providing emergency

shelter and services temporarily.

HOMELESS DATA

Counting the HomelessGiven that the homeless often lack a xed

address, collecting accurate data on this population is challenging. This

study conducted a web scan of area programs and interviews with key

government stakeholders and nonprot service providers, advocates, and

nonprot developers across the region. Researchers also analyzed data

collected by jurisdictions using local Homeless Management Information

Systems (HMIS) as well as street surveys conducted in late January 2013 as

part of a national Point-in-Time (PIT) count of the homeless coordinated by

HUD. In addition to the federally-mandated PIT count every two years, the

Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments coordinates jurisdictions

in the Washington region to conduct an annual count. Because the PIT

count occurs on a single night, it serves as a snapshot of the homeless

on that night only and therefore does not reect the total number of

people who experience homelessness over the course of the year.

Continuum of CareTo better coordinate funding and services, local

homeless service providers are usually organized into a Continuum of

Care (CoC), which is made up of local government agencies and nonprot

service providers. CoCs are responsible for collecting the data during

the PIT count. In the Washington region, CoCs are organized by county

except in a few cases. The independent cities of Fairfax City and Falls

Church are included in the Fairfax County CoC (and labeled Fairfax in

this study), and the cities of Manassas and Manassas Park are included

in the Prince William County CoC (and labeled Prince William).

15 This study classied people as homeless if they met the HUD denition of an individual or family who lacks a xed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, meaning: (i) Has a primary nighttime

residence that is a public or private place not meant for human habitation; (ii) Is living in a publicly or privately operated shelter designated to provide temporary living arrangements (including

congregate shelters, transitional housing, and hotels and motels paid for by charitable organizations or by federal, state, and local government programs); or (iii) Is exiting an institution where (s)

he has resided for 90 days or less and who resided in an emergency shelter or place not meant for human habitation immediately before entering that institution. (Retrieved from https://www.

onecpd.info/resources/documents/HomelessDenition_RecordkeepingRequirementsandCriteria.pdf on November 12, 2013.) While HUD does not include adults with children in its denition

of chronic homelessness, it does include either (1) an unaccompanied homeless individual with a disabling condition who has been continuously homeless for a year or more, OR (2) an

unaccompanied individual with a disabling condition who has had at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three years (HUD 2007). Homeless families were included in this study as

chronically homeless if the adult in the family met the criteria. Research shows that the chronically homeless are best served by permanent supportive housing, which provides services along with

an afordable housing unit (Culhane, Metraux, and Hadley 2002; Larimer et al. 2009; Martinez and Burt 2006).

HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION 12

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

HOW MANY HOMELESS

PEOPLE LIVE IN THE REGION?

In January 2013, 11,245 persons were

homeless in the Washington region.

Of those, 5,944 were single adults

and 5,301 were in families (table

2.1).

16, 17

At 47 percent, the Washington

region has a larger share of families

among its homeless population than

the national average (37 percent).

18

The majority of homeless were

sheltered on the night of the

Point-in-Time (PIT) Count of the

homeless (see box Homeless Data

for more information). However,

11 percent (1,259 persons) were

living on the street and not in

emergency shelter or transi-

tional housing. Living on the street

without shelter was more common

among single adults than families.

More than 20 percent of homeless

single adults (1,250 persons) were

unsheltered and living on the streets,

compared with less than 1 percent

of persons in families (9 persons).

Approximately one-fourth of the

homelessor 2,912 peoplewere

chronically homeless in 2013. The

incidence of chronic homelessness

is much higher (44 percent) among

single adults. In contrast, just 6 percent

of homeless persons in families

were chronically homeless. As noted

earlier, the chronically homeless

represent the group most in need

of permanent supportive housing.

16 Throughout this study, persons in adult-only households are referred to as single adults. Among the homeless, almost all adult-only households

are single adults.

17 Data from the 2014 Point-in-Time count of the homeless were not available when the analysis for this study was conducted. Findings based on

2013 data are consistent with conclusions that might be drawn from the 2014 data. On January 29, 2014, 11,946 people were homeless in the

Washington region, including 6,057 single adults and 5,880 persons in families.

18 This value includes Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories and is based on HUDs 2013 national Point-in-Time Count, the most recent data

available. Data retrieved from https://www.onecpd.info/reports/CoC_PopSub_NatlTerrDC_2013.pdf on December 4, 2013.

HOMELESS YOUTH

Despite the importance of providing

services and interventions to

homeless youth living on their own,

homeless youth are not included in

this study because estimates of this

population are so unreliable. National

estimates vary from a low of 22,700

to a high of 1.67 million homeless

children and youth under the age

of 18 in households with no adults.

Homeless single adults and persons in

families are easier to count because

they are more likely to be in shelters

or connected to service programs.

In contrast, child-only households

are a transient population that often

avoids mainstream services because

of a distrust of authority, fear of being

returned to their previous situation, or

a desire to avoid foster care.

The Point-in-Time Count process

currently the most accurate

national method of measuring

homelessnessdoes not provide

much information about the scope

of homelessness among youth and

which youth are most afected.

To address this gap, the Obama

administration has promised to

end homelessness among families,

children, and youth by 2020. Several

federal agencies collaborated

in 201213 to create the Youth

Count! Program, a youth homeless

count in nine sites across the

country. Although a recent report

detailed promising practices and

potential improvements to the

processes and some jurisdictions

continue to conduct youth counts

independently, these eforts remain

uncoordinated and difcult to

compare across jurisdictions.

Source: Pergamit et al. (2013).

Photo: K. Wags

13 HOUSING SECURITY IN THE WASHINGTON REGION

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE until 12:01 a.m. EDT July 15, 2014

What is the size of the homeless

population in each jurisdiction?

The size of the homeless population

varies widely by jurisdiction in the

Washington region. The District of

Columbia had the largest homeless

population (6,859 persons), more